No place to hide

George Kessarios

Chief Economist & Fund Manager

What is the Fed trying to do?

Analysts, pundits, and Central Bankers are mostly right when it comes to economic issues, growth, and inflation. However, their models do not include a pandemic or war. As such, most estimates and projections during the past several months may be treated with skepticism. In fact, market participants have for the most part been positively surprised by most economies, as opposed to the doom and gloom that was forecasted at the start of the pandemic.

But in order to avert a depression, central banks and governments came to the rescue. Central Banks intervened with liquidity and loose economic conditions (lower interest rates and ample liquidity), and governments gave cash handouts to make up for the loss of income.

Now the Fed wants to take everything back. At least that’s what they mean when they want to reduce the Fed’s balance sheet. But there is a small problem. As a general rule of thumb when liquidity is created, it eventually gets backed in the system, and any attempt to take it out again (shrink the balance sheet) causes a lot of harm to the economy and markets.

Will higher rates reduce inflation?

As you all know, there have been many supply-side disturbances because of the COVID pandemic. These supply issues and bottlenecks have in many instances raised prices, caused delays in procurement, or simply made products unavailable. As a result, prices for many products and services have gone up. In fact, higher than originally thought, and longer in duration..

However, COVID price rises were not the end of the world and didn’t bite into consumer purchasing power all that much. The main problem with current inflation dynamics relates to energy costs and commodities. The current rise in energy costs is responsible for a much broader rise in goods and services, as opposed to a rise in computer chips.

As an example, a price-rise in a particular computer chip because of a supply side disturbance, only raises the cost in the specific product in which it is used. A rise in oil and gas prices, raise the price of gas that affects consumers, the cost of transportation, the cost of international shipping, air-travel, and even commodities because of all the reasons mentioned. However, let me make two observations.

First, the higher cost of energy is not so much because of an increase in demand, but of lack of supply. The lack of supply however is mostly because of geopolitical turmoil (Russian – Ukraine war). In fact, in many cases these price increases are self-afflicted, because many governments have decided to limit or prohibit Russian energy imports in their countries. Energy prices will eventually come down, but only after Russian oil returns to the market, or an increase in supply comes from another source, or if current producers produce more oil and gas.

In other words, there is not much the Fed can do to lower energy prices, outside of technically crashing the US economy with very high rates. As such, is doubtful if the monetary policy is an answer to current inflation dynamics.

The Fed does not have any easy options.

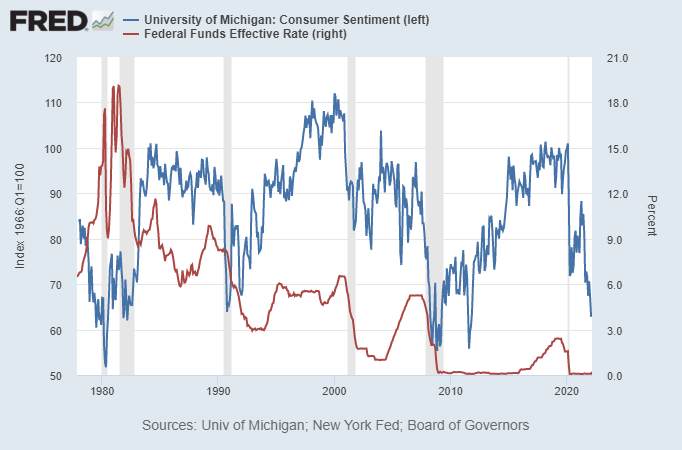

As you can see from the chart below, consumer sentiment is approaching the lows of the 2008 financial crisis, and only 3 times during the past 40 years has sentiment been so low.

Obviously, the main culprit for such a low sentiment reading is inflation, eating into consumer disposal income. However, what would happen if consumers had even less disposal income because of higher mortgage rates, higher credit costs to buy a car, higher credit card rates, and a many other costs that have to do with higher interest rates?

The answer is probably an even lower consumer sentiment reading, and lower demand. However, lower aggregate demand is what the Fed wants to achieve to lower inflation. By elevating interest rates the Fed can eventually achieve such a goal. Some market participants, however, are skeptical if the price of energy will fall in the absence of an increase in supply.

The Fed aims to achieve lower inflation but without inducing a recession. With consumer sentiment being so low, a soft landing is a very speculative bet. And while nobody knows what the outcome of the Fed’s policies will be, the most probable result will be recession, if it raises rates by 50 basis points several times in a row and shrinks its balance sheet as it has said it will. Obviously, another sector of the US economy that will be affected is housing.

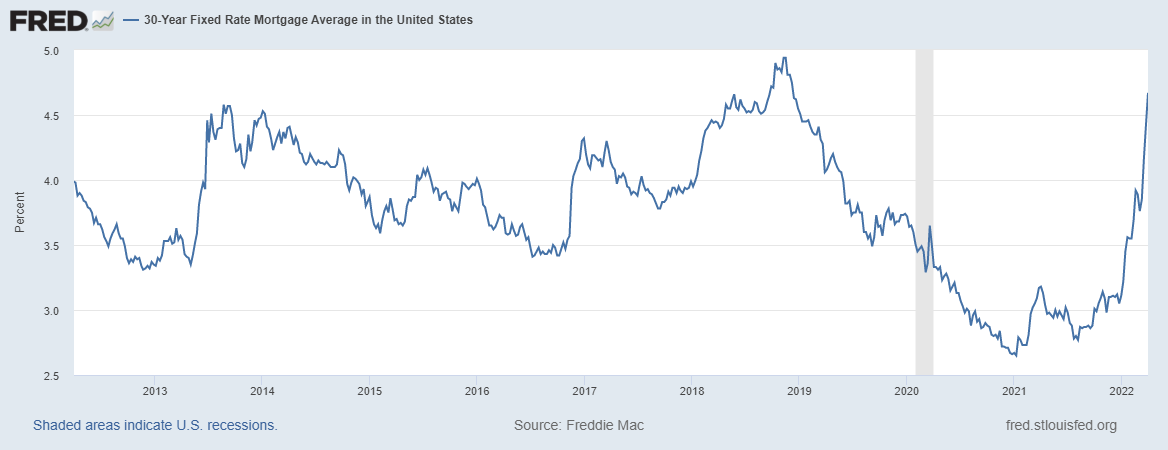

As illustrated on the chart above, the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate is already approaching 5%. There’s an increased probability, when mortgage rates stay elevated long enough, the US housing may break. Is monetary policy the answer?

On the other hand, politicians on both side of the Atlantic are calling for Central Banks to do something about higher prices. Central Banks have been pressured for a while, with many accusing them of being behind the curve.

The problem however is that higher rates might not be the answer. In the absence of a pandemic and war, it is true that monetary policy would have been the answer to an economy that is overheating. However how can monetary policy lower higher energy prices, when there is a lack of supply, or supply side shortages because of the COVID pandemic, something that is still ongoing? This is something that many analysts and economists are trying to figure out. And the truth is that there are no easy answers.

Why does the Fed want to reduce its balance sheet?

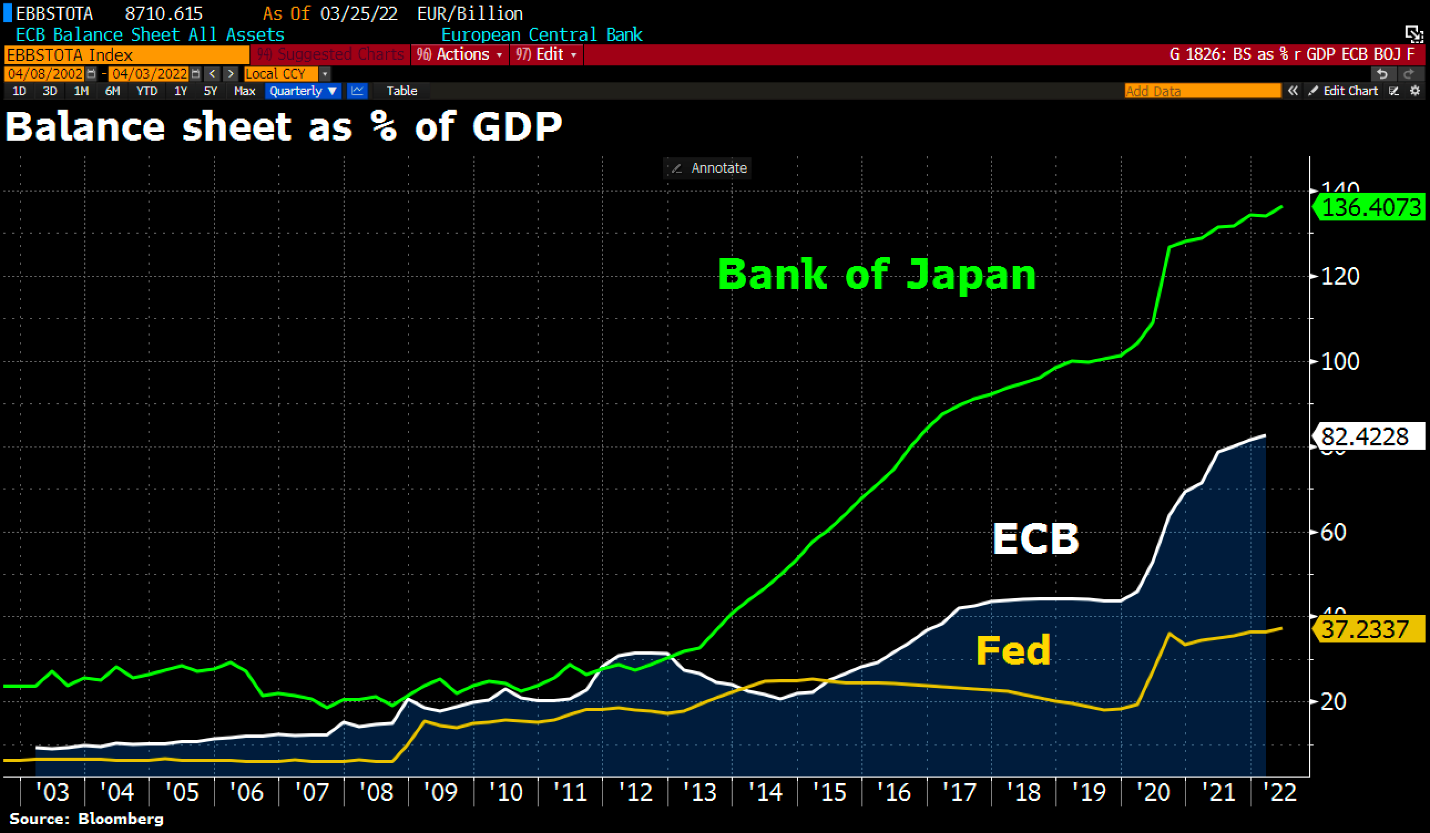

First of all, for all the concern pertaining to the Fed’s balance sheet, very few mentions are made about the balance sheet of the ECB or the BoJ. As the chart above shows, as a percentage of GDP, the ECB has more than double the Fed’s balance sheet, and the BoJ almost 4 times the balance sheet of the Fed. So, my question is, why does the Fed think its balance sheet must shrink? Furthermore, how is this connected with its goal to reduce inflation?

This is not an easy question to answer, because nobody knows what is in the Fed’s mind. However, everybody knows that inflation as presented in the article found on the company’s internet side here in both Europe and Japan has not been a function of their balance sheets all these years. As such, there are reservations if the Fed’s balance sheet has anything to do with inflation.

As mentioned above, once liquidity is created it gets backed into the system, it is very difficult to unwind, and it might cause a lot more damage than the benefit of lower inflation. Also, the unwinding of the balance sheet acts like using leverage trade in reverse. In other words, the damage could be much more painful than we could imagine, if the Fed allows its balance sheet to unwind to the tune of about $1 trillion per year.

Bond market shakeout

It does not take much to figure out the kind of carnage bonds might face if the Fed raises rates as advertised with yields so low. According to a recent Financial Times article, “Treasuries set to post worst quarter of returns since at least 1973 on inflation and rate rise fears”.

Indicative of the carnage is the chart below (from Bloomberg).

The price of Austria’s 100-year bond has more than halved in price. After starting at around 110 in 2020, investors holding these bonds have lost around 40%. Not from the highs, but from their initial investment.

The Fed has reiterated via proxy (ex-Fed officials) that it wants to take the market down, to take away the wealth effect created by the market. The logic being, if everyone feels poor, they will curtail spending. Well, insofar as bonds are concerned, the Fed is doing a great job.

But how much fixed income carnage is the Fed willing to tolerate in the name of lower inflation? Impossible to know, but please keep in mind that many have characterized the current Fed as the most hawkish since Paul Volker.

Chairman Powell has suggested that QT (quantitative tightening) will proceed at about $1 trillion per year. Taking into account the addition to the QT of the expected net issuance by the US Treasury at around $1,5 trillion per year, market forces (or non-Fed buyers) are expected to purchase about $2 trillion on average for the next 3 years. It is not sure where this money will come from neither the yield that this debt will maintain.

So, as bad as the bond market seems at the moment, if the Fed’s playbook materializes, we might just be in the beginning of a lot more pain for bonds.

The bottom line

Be it stocks or bonds, if the Fed delivers on its threat to increase interest rates as it has hinted ( 2.25% - 2.50%), investors have no place to hide. There are no safe havens at the moment, not to mention that sentiment is limit down.

Also, this is still a very expensive market. Not so much at the average stock level, but at the mega cap and index level. I would be a lot calmer if the S&P 500 Index had a 15 multiple, but instead its trailing multiple is around 24, with the forward multiple at around 20.

Now having said all this, I do not believe that the Fed will be able to raise rates past 1.5%. The reason is that it will probably cause a lot more damage than the benefit. Also, one thing that seems wrong about current Fed policy is that it is aiming at inflation instead of growth.

Hawkish monetary policy usually aims at cooling down the economy. This colling down is expected to lower inflation and inflation expectations. This time around the Fed is aiming at inflation with a disrespect for growth. Furthermore, the Fed has a total disrespect for the market and the wealth effect.

At some point, I think the Fed will notice the damage being done and do an about face. But the question is how much damage will be done until then, and how long will it take for the Fed realize this. I do not have an answer, but my target as I said is the 1.5% mark.

Finally, remember that the market is forward looking. At some point, even as monetary policy continues its path, markets will bottom out. But trying to time the market at the moment, while the covid pandemic is still in play, with geopolitical turmoil in full blown mode, and with perhaps the most hawkish Fed sine Paul Volker, is an impossible task.

Important Information: This communication is marketing material. The views and opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) on this page, and may not necessarily represent views expressed or reflected in other Exclusive Capital communications, strategies or funds. This material is intended to be for information purposes only and is not intended as promotional material in any respect. The material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument.